Risks Related to Development, Clinical Testing, Manufacturing and Regulatory Approval

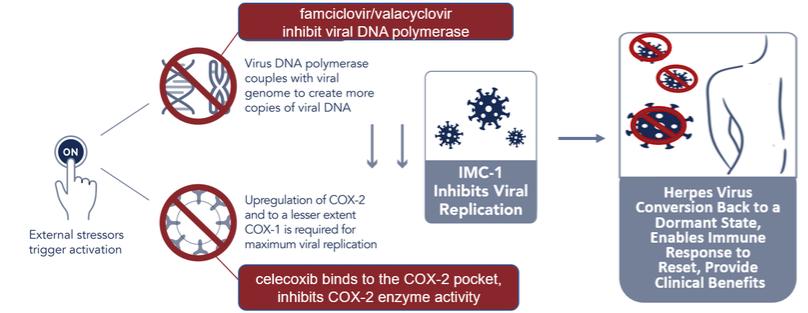

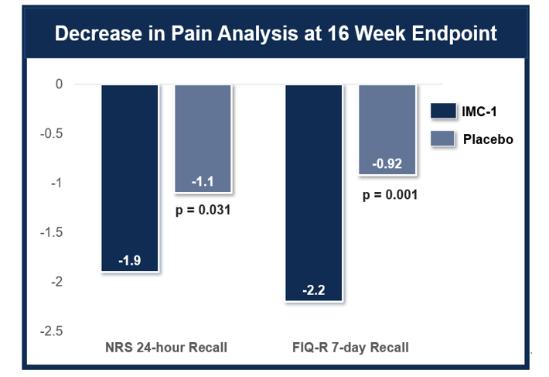

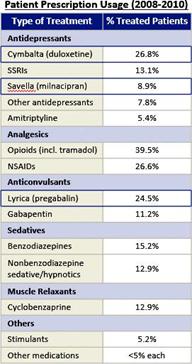

We are heavily dependent on the success of IMC-1, our most advanced candidate, which is still under clinical development, and if this drug does not receive regulatory approval or is not successfully commercialized, our business may be harmed.

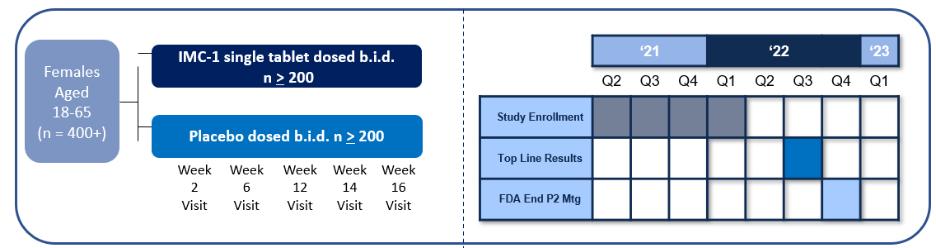

We do not have any products that have gained regulatory approval. Currently, our lead development-stage candidate is IMC-1. As a result, our business is dependent on our ability to successfully complete clinical development of, obtain regulatory approval for, and, if approved, successfully commercialize IMC-1 in a timely manner. We cannot commercialize IMC-1 in the United States without first obtaining regulatory approval from the FDA; similarly, we cannot commercialize IMC-1 outside of the United States without obtaining regulatory approval from comparable foreign regulatory authorities. Before obtaining regulatory approvals for the commercial sale of IMC-1 for a target indication, we must demonstrate with substantial evidence gathered in preclinical studies and clinical trials, generally including two adequate and well-controlled clinical trials, and, with respect to approval in the United States, to the satisfaction of the FDA, that IMC-1 is safe and effective for use for that target indication and that the manufacturing facilities, processes and controls are adequate. Even if IMC-1 were to successfully obtain approval from the FDA and comparable foreign regulatory authorities, any approval might contain significant limitations related to use restrictions for specified age groups, warnings, precautions or contraindications, or may be subject to burdensome post-approval study or risk management requirements. If we are unable to obtain regulatory approval for IMC-1 in one or more jurisdictions, or any approval contains significant limitations, we may not be able to obtain sufficient funding or generate sufficient revenue to continue the development of any other candidate that we may in-license, develop or acquire in the future. Furthermore, even if we obtain regulatory approval for IMC-1, we will still need to develop a commercial organization, establish commercially viable pricing and obtain approval for adequate reimbursement from third-party and government payors. If we are unable to successfully commercialize IMC-1, we may not be able to earn sufficient revenue to continue our business.

We may face future business disruption and related risks resulting from the ongoing outbreak of the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) or from another pandemic, epidemic or outbreak of an infectious disease, any of which could have a material adverse effect on our business.

The development of our drug candidates could be disrupted and materially adversely affected in the future by a pandemic, epidemic or outbreak of an infectious disease like the ongoing outbreak of COVID-19. In December 2019, a novel strain of coronavirus was reported to have surfaced in Wuhan, China, which has and is continuing to spread throughout the world, including the United States. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization characterized the outbreak as a “pandemic”. The significant outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in a widespread health crisis, has adversely affected the economies and financial markets worldwide, and could adversely affect our business, results of operations and financial condition. More recently, in 2021, a “Delta” variant and subsequent “Omicron” variant of the COVID-19 virus has reignited concerns of a new or more contagious spread of the virus as a result of these, or any additional, variants.

The spread of an infectious disease, including COVID-19, may also result in the inability of our suppliers to deliver components or raw materials on a timely basis or materially and adversely affect our collaborators and out-license partners’ ability to perform preclinical studies and clinical trials. In addition, hospitals may reduce staffing and reduce or postpone certain treatments in response to the spread of an infectious disease. Such events may result in a period of business and manufacturing disruption, and in reduced operations, any of which could materially affect our business, financial condition and results of operations.

The ultimate extent of the impact of any epidemic, pandemic or other health crisis, including COVID-19, on our ability to advance the development of our drug candidates, including delays in starting or completing clinical trials, or to raise financing to support the development of our drug candidates, will depend on future developments, which are highly uncertain and cannot be accurately predicted, including new information that may emerge concerning the severity of such epidemic, pandemic or other health crisis and actions taken to contain or prevent their further spread, among others.